Heaven forbid a political candidate’s Facebook account gets hacked. They might spread disinformation…like they’re already allowed to do in Facebook ads…

Today Facebook made a slew of announcements designed to stop 2020 election interference. “The bottom line here is that elections have changed significantly since 2016,” and so has Facebook in response, CEO Mark Zuckerberg said on a call with reporters. “We’ve gone from being on our back foot to proactively going after some of the biggest threats out there.”

One new feature is called Facebook Protect. By hijacking accounts of political candidates or their campaign staff, bad actors can steal sensitive information, expose secrets and spread disinformation. So to safeguard these vulnerable users, Facebook is launching a new program with extra security they can opt into.

Facebook Protect entails requiring two-factor authentication, and having Facebook monitor for hacking attempts like suspicious logins. Facebook can then inform the rest of an organization and investigate if it sees one member under attack.

Today’s other announcements include:

- The takedown of foreign influence campaigns, three from Iran and one from Russia in order to protect users from deception.

- Labeling state-owned or controlled media organizations like Russia Today on their Facebook Pages and the Ad Library to help users identify potential propaganda.

- Added Page ownership transparency for ePages with large U.S. audiences and those verified to run political ads, which will have to display their owner’s organization’s legal name, city and phone number or website so it’s clear where information comes from.

- New transparency features around political ad spend, including a U.S. presidential candidate spend tracker, more geographic spending details, info on which apps an ad appears on and programmatic access to downloads of political ad creative.

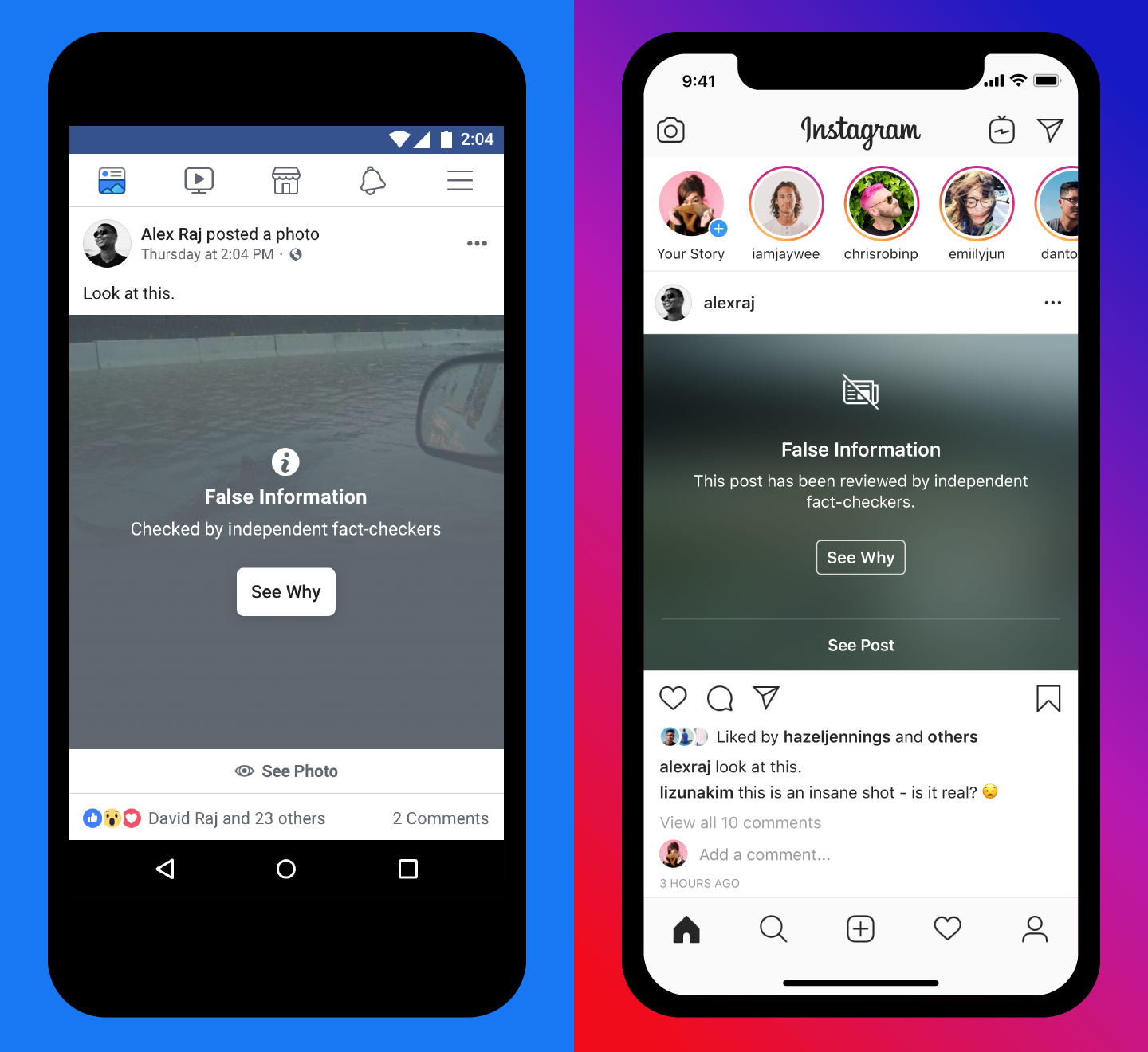

- Much more prominent fact-checking labels will now run as interstitials warnings atop photos and videos on Facebook and Instagram that were fact-checked as false, rather than smaller labels attached below the post to make sure users know information is false before consuming it. Users will also be warned before they share posts fact-checked as false to keep them from going viral.

- A wider ban on voter suppression ads that suggest it’s useless to vote, provide inaccurate polling or voter eligibility information or threaten people if they vote or based on the outcome of an election to prevent intimidation and confusion.

- A $2 million investment from Facebook into media literacy projects to develop new methods of educating people to understand political social media and ads.

- Facebook Protect offering hack monitoring services to elected officials, candidates’ political party committees, government agencies and departments surrounding elections and verified users involved in elections.

![]()

Combined, the efforts could protect both campaigns and constituents from misinformation while giving everyone more clarity about where content originates. Yet the approach highlights Facebook’s tightrope walk between policing its networks and overstepping into censorship.

In a speech last week, Zuckerberg tried to firmly plant Facebook as erring on the side of giving people a voice rather than stifling speech. He raised the threat of China’s influence over foreign businesses by dangling its giant market in exchange for adherence to its political values. And he tried to defend allowing lies in political ads, arguing that banning political ads on Facebook as I’ve recommended the company do would benefit incumbents and silence challengers who don’t have media attention.

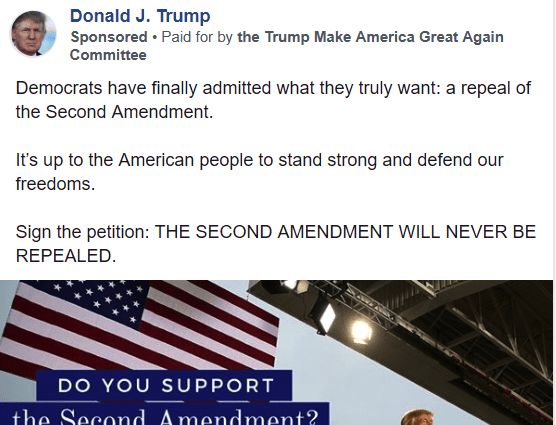

A Trump ad spreads misinformation claiming Democrats want to repeal the second amendment

Yet throughout the call, Zuckerberg was hammered with questions about Facebook’s willingness to fact check what users share with friends, but not what politicians pay to show to millions of voters.

“People should make up their own minds about what candidates are credible. I don’t think those determinations should come from tech companies . . . People need to be able to see this content for themselves,” Zuckerberg insisted. Yet if Facebook is willing to cover photos containing misinformation with a warning label you have to click to see past, it’s strange that it’s unwilling to do the same for political ads.

Like farming out fact-checking to third-party news outlets as Facebook already does, banning political ads wouldn’t force Facebook to judge the truth of individual statements, and they’d still have the right to share what they want to their own followers.

When I asked why he believes banning political ads would favor incumbents, Zuckerberg admitted, “You’re right that incumbents can raise more money,” and he wasn’t sure there’d been a comprehensive study on the matter. His defense relied on anecdotal beliefs of unnamed sources:

I’ve talked to a lot of people. The general belief that they have, when they’re a challenger, is that they rely on different mechanisms like ads in order to get their voices into a debate more than incumbents do . . .

From all of the conversations that I’ve had, the general overwhelming consensus from people who are participating in these things and who work on them has been that removing political ads would favor incumbents.

While the rest of Facebook’s announcements today felt like sensible steps in the right direction, the company will need stronger arguments for why it polices misinformation shared by users but not political ad campaigns.

If it wants to find a better middle-ground, it could offer standardized ad units for political campaigns that endorse the candidate and ask for donations, but can’t make potentially untruthful assertions about them or their competitors. Alternatively it could apply fact-check labels to political ads without making calls of veracity itself. Facebook could also build other ways for challengers to grow their voice outside of ads so it could ban them without supposedly empowering incumbents.

Otherwise, it faces a political ad misinformation arms race in stern contrast to its other pro-truth efforts announced today. What will Facebook do if campaigns make increasingly malicious and inaccurate statements about their rivals via ads, claiming only donations to their candidate can save society? And what if they keep pouring all the money they unscrupulously raise into more ads? “My opponent eats babies. Donate to me by midnight. Only I can stop them from becoming America’s dictator.”

At least most of the time, users can try to avoid politics by ignoring campaign pages and unfollowing their crazy uncles. But untrue ads inject polarization and discord into people’s feeds. Facebook’s policies give the richest, most craven candidates the loudest voices. Can the social network and the democratic process survive a whole year of top spenders shouting lies?